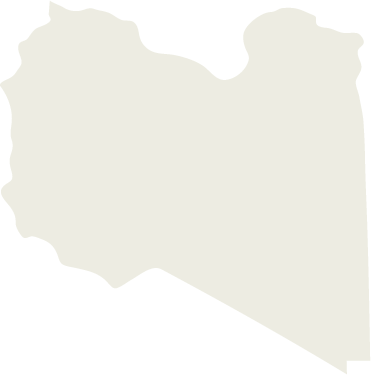

Saul Meghnagi was born in Tripoli in 1946, shortly after the end of World War II, into a family of Libyan origin whose roots trace back to the sixteenth century. The Meghnagi family—parents Joseph and Rosina Haggiag, Saul, and his sisters—lived in an apartment on Corso Sicilia, which was renamed Sharia al-Mizran after the end of the Italian colonial era. The family spoke Italian at home and their culture was predominantly Italian, although the grandparents spoke Arabic and Judeo-Arabic and maintained some Libyan customs.

Saul grew up in a city where Western influences were still very strong: he attended an Italian school and, like many of his generation, he was fascinated by the American music and culture brought by the US military base. He spent most of his time with his schoolmates, enjoyed his free time at the local beach club with his family, and attended parties at friends’ homes. The Meghnagi family celebrated Jewish holidays and attended the synagogue, keeping kosher and observing the Sabbath, although like many other Tripolitan families, they indulged in “small transgressions,” such as using the car.

In 1964, Saul moved to Rome to attend university, enrolling in the faculty of engineering. His early days in the Italian capital were difficult, but he strengthened his bonds with other young Jewish Tripolitans who, like him, had moved to Rome to study. Like many of his peers, Saul hoped to pave the way for the rest of his family to move to Italy, but it was the outbreak of the Six-Day War in 1967 and the resulting anti-Jewish violence that forced the rest of the Meghnagi family to leave Tripoli for Rome in July of that year. The family’s situation, like that of many other Jews who fled Libya at that time, was further complicated by their precarious legal status. Like many Libyan Jews, they had no recognized citizenship: they could only travel with a “Temporary Travel Document,” which allowed them to travel to certain countries, but not others, and was valid for six months, after which the sole way to renew it was via the Libyan authorities.

we were Libyan citizens de jure, but not de facto

Transcript

Interviewer

What nationality did [your family] have?

Saul Meghnagi

I can answer legally. As I came to understand precisely when I arrived in Italy, we were Libyan citizens de jure, but not de facto. By the way, if you’d like, I could show you the certificate from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which recognized us as refugees, a legal status that was never acknowledged by the Italian authorities.

Interviewer

So you weren’t even declared stateless?

Saul Meghnagi

No.

Interviewer

You were nothing?

Saul Meghnagi

Yes. In fact, we acquired Italian citizenship after ten years, in ’77, as ex-Libyans, but the condition we found ourselves in was that of holders of a temporary travel document, which had two characteristics. One was that the first page had the “ya,” the initial of the word “yahudi” (Jew), which I found in a Libyan passport belonging to an uncle who actually had a passport. It was even present in some Libyan passports. [The second characteristic was] the duration, which was generally a maximum of six months.

Interviewer

So, could it be said that Libyan Jews in Libya were not considered citizens? Not even second-class citizens, nothing, not even dhimmi?

Saul Meghnagi

No, we had no recognized legal status, and as far as I know, there was no regulation that defined this anomalous condition. It was a common practice, but it had no explicit legal basis. At least that’s what we were told by the Italian authorities, who didn’t recognize us as refugees because, according to them, there was no Libyan law that defined us as such. So, for them, we were Libyan, despite the curious document we had.

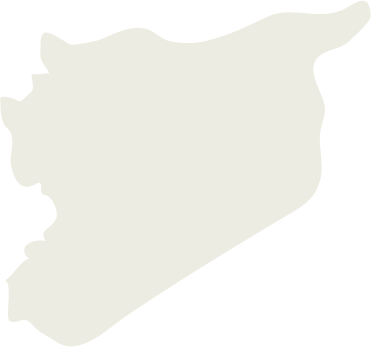

After the family’s arrival in Italy, Saul changed his course of study and decided to deepen his knowledge of Hebrew in Israel, at an ulpan in Arad, in the southern part of the country. He was admitted to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, but his lack of stable citizenship prevented him from staying there. Returning to Rome, he obtained a scholarship from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Italian Jewish Assistance Agency, enrolling in a social work school. After graduating, he resumed his academic studies, earning a degree in philosophy and a doctorate in educational sciences.

During these years, Saul became actively involved in the Italian Jewish community, contributing to the creation of the Jewish Cultural Center, a family counseling center, and services for Jewish refugees in transit from the USSR to the United States. With the support of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Saul participated in youth training and community-building programs that were designed for Italian Jewish communities, solidifying his role in the community.

during those years, the American Joint began this professionalization, as they called it, of the Jewish communities

Transcript

Saul Meghnagi:

I was entrusted with Kadima, the youth organization. This was because at that stage – maybe at the CDEC you will have more precise dates – but in those years, the American Joint was strongly engaged in the development of youth activities in Europe for the rebuilding of Jewish communities that had suffered the tragedy of the Shoah. Also, in those years, there were two events. This was in the early seventies, I graduated in the early seventies. [Two things happened]: one was the agreements with Germany for the compensation distributed by the [Claims Conference], which supported – also in Milan, [but] definitely in Rome – the establishment of the Jewish Cultural Center and the family counseling center. [The second thing] was the arrival of Jews from the Soviet Union on their way to the United States. During those years, the American Joint began this professionalization, as they called it, of the Jewish communities, meaning the training of young leaders in the communities, and I was involved with this effort. I must say, it was an extraordinary opportunity professionally, because the director of the Community Center in Minneapolis was sent to Rome. He had a reputation as a designer of educational and cultural activities in the Jewish field. He stayed in Rome for a year, and I was fortunate enough to be his official translator and guide, so I learned the profession and some methods from this experience. I then participated in the planning of this Jewish Cultural Center, which still exists today.

Since 1978, Meghnagi has continued his career in vocational education in the trade union field. The Institute for Economic and Social Research tasked him with designing the Higher Institute for Training, of which he later became president. After the agreement between the state and the Union of Jewish Communities (1987), he became personally involved in the activities of the Union of Italian Jewish Communities, first as cultural commissioner and then as a councilor. From his marriage with Anna Palagi, two children were born.