Italy and Jewish Migrations in the Twentieth Century

Exiles, Deportees, Refugees, Immigrants

In the first half of the twentieth century, Italy served as an important transit point for numerous migratory flows, gradually evolving into a stable immigration destination after World War II. Among those who passed through the country were many Jews fleeing persecution, political instability, or seeking new opportunities. As demographic studies show, a notable aspect of this dynamic is that, despite being a minority, the Jewish population in Italy at times grew at a higher rate than the general population, primarily due to migratory flows.

In the 1911 census, there were about 34,000 Jews in Italy, a number that rose to over 45,000 by the time of the 1938 “racial census.” During those years, with the arrival of exiles from Nazi Germany, the proportion of foreign Jews increased from 4.5% to 20%. However, due to emigration, anti-Jewish persecution, deportations, and losses during the Shoah, the number of Jews in Italy dropped to about 26,000 by the end of World War II.

The postwar period saw a new increase, due to an unprecedented wave of Jewish refugees: it is estimated that between 1945 and 1948, around 50,000 people passed through Italy. After this phase, it was only in 1975 that the Italian Jewish community reached its historical peak, with about 35,000 members—mainly due to immigration from North African and Middle Eastern countries.

This phenomenon, which developed alongside internal migrations, was accompanied by a geographical redistribution of Jewish communities across the country. Over the decades, many of these communities shrank or disappeared entirely, dropping from 87 in 1840 to 21 today. Although most are now small, two communities expanded considerably: that of Rome, due to natural population growth, and that of Milan, thanks to immigration from other parts of Italy and abroad. Between the beginning of the century and the mid-1970s, the Jewish population in Rome doubled, while in Milan it tripled.

From the 1980s onward, the Jewish community in Italy began to shrink, with its size now estimated at about 27,000 people. This decline is due to multiple factors, primarily demographic trends common to the broader Italian population, such as low birth rates and significant aging. Additionally, certain aspects specific to Italian Jewry—such as exogamy, families choosing not to engage with Jewish community life or identity, and emigration (especially to Israel, with 8,233 people leaving between 1948 and 2022)—also contributed.

Jewish Migrations in the First Half of the Century

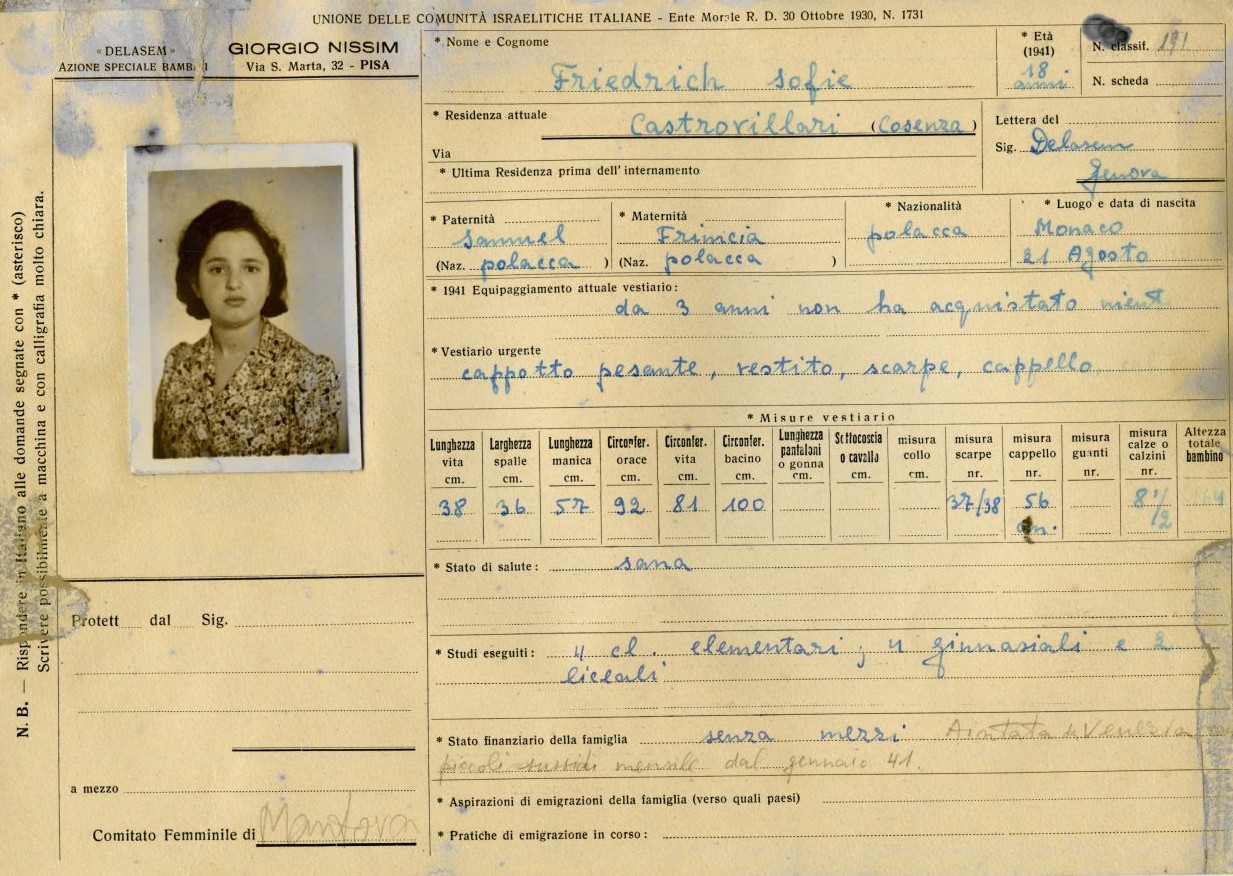

At the beginning of the twentieth century, although limited in number, the first migratory wave arrived mainly from the Balkans, Turkey, and the Dodecanese, driven by economic motives and the geopolitical instability of the region at that time. Jewish emigration from the territories of the Ottoman Empire had begun in the late 19th century, primarily heading to Argentina, the United States, and the Belgian Congo, later extending to Europe, especially France, and more modestly to Italy. For some migrants, cultural and economic ties with Italy, the country’s relatively open stance on migration and employment, and, in some cases, Italian citizenship, facilitated settlement. According to the 1911 census of the Kingdom of Italy, there were only 1,499 foreign Jews in the country, out of a total Jewish population of about 34,000. Twenty years later, in the 1931 census, their number had risen to 5,395 out of 44,507. However, it was only from the late 1930s that the presence of foreign Jews in Italy increased significantly, primarily due to the arrival of Jews fleeing Central and later Eastern Europe. With the rise of National Socialism, Jewish immigration to Italy rapidly increased, reaching 9,415 according to the 1938 racial census. Many arrived intending to leave Europe altogether, supported by the Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants, established by the Union of Italian Jewish Communities.

This migratory phenomenon should not be interpreted as a sign of deliberate Italian openness to the needs of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. It was more a result of the Fascist regime maintaining a relatively liberal stance on foreign entry until almost the start of the war, making Italy one of the few accessible escape routes as many countries closed their borders to immigration.

In 1938, following the enactment of the racial laws and a decree of expulsion requiring all those who arrived after January 1919 to leave the country (including the colonies) by March 1939, many Jews were forced to depart. At the same time, seeking to benefit from the tourism industry, the Fascist regime introduced a visa for those who could prove they were in transit or traveling for health or business reasons. Within six months, about 5,000 Jews entered Italy using this strategy, and between 1938 and 1940, around 10,000–11,000 foreign Jews left Italy via its ports, taking advantage of ongoing civilian maritime traffic.

In June 1940, with Italy’s entry into World War II, foreign Jews still in the country—now considered “enemy aliens”—were interned in camps or subjected to house arrest. It is estimated that until 1943, about 6,000 foreign Jews were interned in Italy. After the armistice of September 8, 1943, those interned in Southern Italy were freed as Allied forces advanced from North Africa. Conversely, those in Nazi-occupied areas under the Italian Social Republic were arrested and deported, along with Italian Jews.

At the end of the war, as Jewish humanitarian organizations and Italian communities engaged in the complex task of rebuilding Jewish life and supporting survivors, Italy again became a major transit point for an unprecedented influx of Jewish refugees. From the summer of 1945, thousands of Holocaust survivors joined those who had escaped deportation, crossing the Alpine passes into Italy with hopes of boarding ships organized by the Mossad Le-Aliyah Bet. This was the secret arm of the Jewish Agency, which since 1943 had based its operations in Italy to organize clandestine immigration to British Mandatory Palestine.

At that time, the 1939 White Paper policy was still in effect, severely limiting Jewish immigration in an effort by British authorities to maintain control over the territory.

By late 1946, the number of Jewish refugees—mostly from Eastern Europe—had peaked at over 26,000. This number began to decline starting in 1948, as the creation of the State of Israel accelerated aliyah. However, until the early 1950s, a minority of refugees remained in Italy temporarily, awaiting departure to destinations such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and South America.

Immigration from North Africa and the Middle East

Between the late 1940s and early 1950s, alongside the influx of refugees from Eastern Europe, Jewish communities and welfare organizations in Italy began registering the presence of dozens of Jews from North Africa, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq. These migratory flows marked a significant shift on two fronts: first, whereas postwar Italy had been primarily a transit country, it now became a destination for immigration; second, while earlier migrations had been primarily European, these new waves came—albeit in smaller numbers but with greater continuity—from across North Africa and the Middle East.

With decolonization, political-military crises, and tensions related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Jewish mobility from the southern and eastern Mediterranean intensified through the late 1970s. Once again, for some, Italy was a temporary stop; for others, it became a permanent destination.

More broadly, from the postwar period onward, Italy was not only affected by significant emigration and internal migration but gradually established itself as an immigration country—first for people from former European colonies in Africa and the Middle East, and later from Europe as well.

Demographic studies on Italy’s Jewish population show that the proportion of foreign-born Jews rose from just over 2% in the early twentieth century to 27% in 1975. Specifically, the share of immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East rose from 30% in the 1945–1955 period to nearly 70% between 1955 and 1965.

From the late 1950s onward, the first significant migratory flow involved Iranian Jews, primarily from Tehran but descended from the Mashhad community, which had been forced to convert in the 19th century. Their presence grew in the 1960s, driven by economic motives and supported by strong family networks. Most settled in Milan, where by the 1980s the community numbered around 1,600 people. At the same time, Jews from Syria and Lebanon also settled in Milan. Though smaller in number—about a hundred people—this migration was also supported by family ties and community networks.

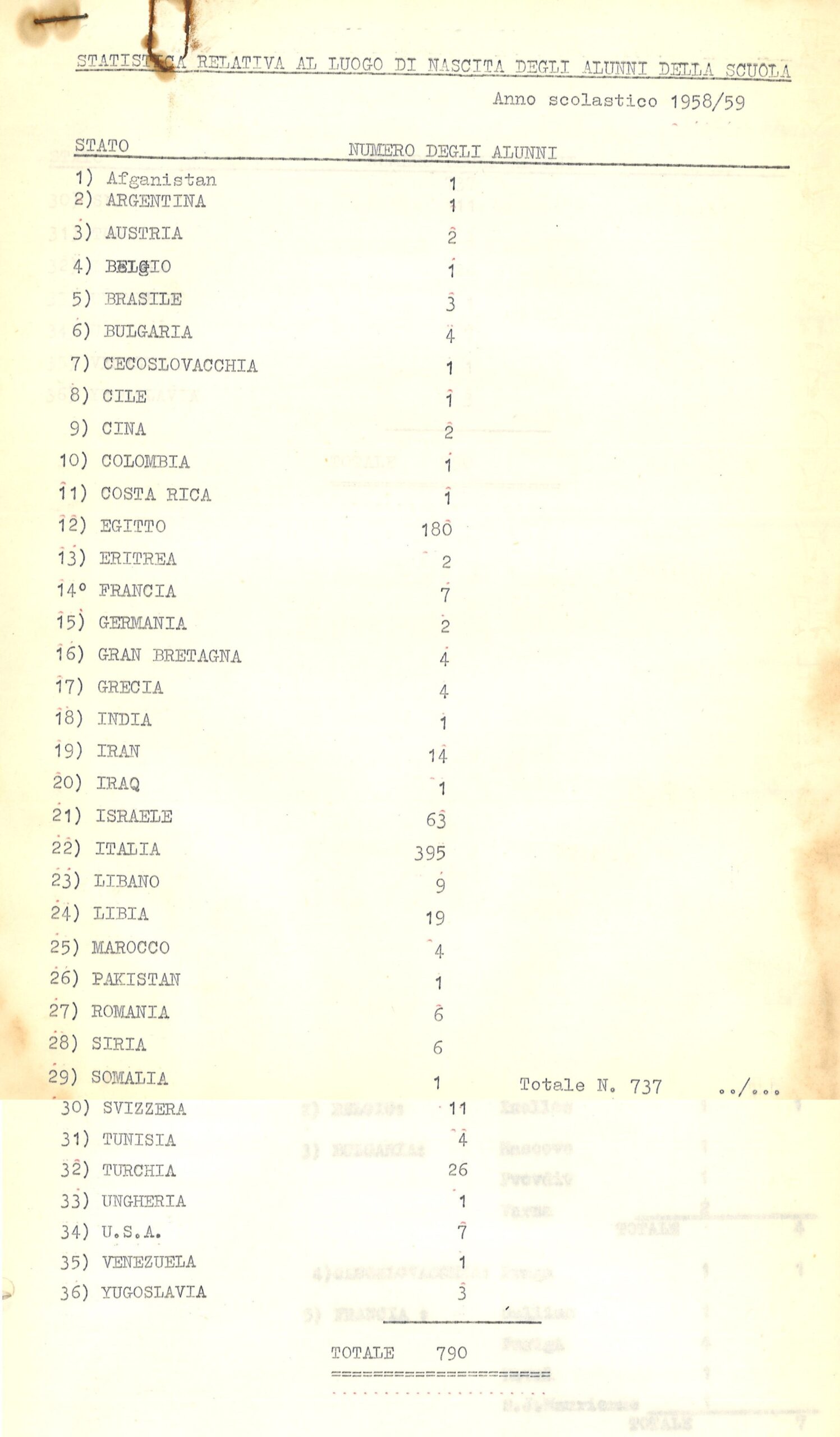

Following the Suez Crisis of October 1956, around 1,000 Jews fleeing Egypt settled in Italy, while many others transited through before emigrating elsewhere. These were mostly middle-class urban families, many of whom held European citizenships—especially Italian—retained through the capitulation system. The majority settled in Milan, where the local Jewish community quickly mobilized to address the humanitarian emergency and support integration. Particular attention was given to the community school system, which, due in part to migration from the Middle East, saw its student body double between 1950 and 1960, from about 400 to 800 pupils.

After the Six-Day War in 1967, a new wave of migration occurred when the Jewish community in Tripoli became the target of violent pogroms, fueled by virulent anti-Jewish and anti-Zionist propaganda following the Arab-Israeli conflict. These attacks caused looting, destruction, dozens of injuries, and around fifteen deaths. As a result, about 4,000 Libyan Jews were forced to flee, initially finding temporary refuge in Italy. On that occasion, the Italian government agreed to temporarily receive the exiles due to ongoing historical ties with the former colony. However, with Muʿammar Gaddafi’s rise to power in 1969 and his expulsion decree of 1970, any hope of returning to Libya was extinguished. Around 1,500 Jewish refugees from Libya opted for permanent resettlement in Italy, primarily in Rome.

Jewish migration to Italy continued from Syria and Lebanon but progressively declined after the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and further with the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. These years marked the mass emigration of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa, leading to the gradual disappearance of Jewish communities in most of those countries.

Throughout the twentieth century, Jewish migrations to Italy occurred within a broader context of mobility triggered by persecution, conflict, political and economic instability, and precarious legal status in countries of origin, often accompanied by a steady erosion of civil rights. Added to these factors were historical ties between Mediterranean Jewish communities and Italy, along with the country’s growing appeal as a destination for immigration. Examining the Jewish migratory flows that passed through the Peninsula over the century reveals the continuity of this phenomenon, which developed with varying intensity and in parallel with other waves of migration that shaped contemporary Italy.

Bibliography and sources

Archivio CDEC, Fondo Comunità ebraica di Milano

Bottecchia Giordano, “‘Radio Le Caire incitait les Libyens à se soulever, à tuer les Juifs, à chasser les Américains’: reflets de la propaganda nassérienne sur les violences de juin 1967 en Libye”, in Studi di Storia Contemporanea, 45-1, 2021, pp. 39‑58.

Colucci Michele, Storia dell’immigrazione straniera in Italia: dal 1945 ai nostri giorni, Carocci, Roma, 2018

Della Pergola Sergio, Anatomia dell’ebraismo italiano: caratteristiche demografiche, economiche, sociali, religiose e politiche di una minoranza, Carucci, Assisi-Roma, 1976

Della Pergola Sergio, Essere Ebrei, oggi: continuità e trasformazione di un’identità, Il mulino, Bologna, 2024

Della Pergola Sergio, “Demografia, economia e società. Le trasformazioni della popolazione ebraica nell’Italia del Novecento”, in V. Bo e M. Toscano, Ebrei nel Novecento Italiano, Sagep editori, Genova, 2024, pp. 24-34

Papo Isacco, “L’immigrazione ebraica in Italia dalla Turchia, dai Balcani e dal Mediterraneo orientale nella prima metà del XX secolo”, in Rassegna Mensile di Israel, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Gennaio – Aprile 2003), pp. 93-126

Renzo Chiara, Jewish displaced persons in Italy, 1943-1951: politics, rehabilitation, identity, Routledge, London-New York, 2024

Rossetto Piera, Juifs de Libye. Constellations de mémoires, Effigi, Arcidosso, 2023

Sarfatti Michele, Gli ebrei nell’Italia fascista. Vicende, identità, persecuzione, Einaudi, Torino, 2018

Voigt Klaus, Il rifugio precario. Gli esuli in Italia dal 1933 al 1945, voll. 1 e 2, La Nuova Italia, Scandicci 1993

Zanini Paolo, “Tra due diaspore: ebrei levantini ed egiziani in Italia (1948-1957)”, in Mediterranea, 19 (2022), n. 54, pp. 41-68.