European citizenship and influences among Jews in the Ottoman Empire

The links between Livorno and the Levant in the early modern era

To understand Italy’s role—as a final destination or temporary transit point—in the emigration movements that affected Middle Eastern and North African Jewish communities during the 20th century, it is necessary to bear in mind certain long-term dynamics that have their roots in the early modern period. It was between the end of the 15th and 16th centuries, in fact, that some Italian ports, particularly but not exclusively Leghorn, became an intermediate stop in the Sephardic diaspora from Spain and Portugal to the Middle East, the Balkans, and North Africa. As a result, many Jews who settled in communities in the Ottoman Empire or North African regencies had and claimed family, linguistic, and cultural ties, more or less direct and deep, with Italy.

Contacts and relations of this kind were reactivated from the 18th century onwards: during that century, and in the first decades of the 19th century, numerous Italian Jews, mainly from Leghorn, settled in Ottoman territories, offering themselves as commercial intermediaries between the declining Ottoman Empire and Europe. Thessaloniki, Constantinople, Smyrna, Alexandria, Tunis, and, to a lesser extent, Aleppo and Cairo became the main destinations of this migratory movement. It was a numerically small but qualitatively significant flow. Fundamental to the success of this migration were both the resourcefulness of Leghorn’s merchants and the breadth of their transnational networks, very often structured on the basis of family networks, as well as the privileged status that the capitulations in force in the Ottoman Empire, progressively extended and strengthened during the 19th century, guaranteed to European residents.

European power politics and the question of citizenship

It was precisely because of this situation of protection and privilege enjoyed by European citizens in the Empire that, since the 18th century, the issue of the nationality of these groups of Jewish merchants and, more generally, of the Jewish minorities present in the Ottoman territories, had become a pressing one. The various European powers competed for the protection of Jewish minorities (and, of course, Christian minorities) subject to Constantinople in order to increase their influence in the area. To this end, many European states readily granted certificates of citizenship or protection even when the real ties of the various communities and families with their supposed home country were very weak or even non-existent. It was thanks to these practices that numerous Ottoman Jewish families obtained, often enjoying it for generations, some European citizenships: in particular, French, British, Austrian and, after 1861, Italian citizenship were widely distributed, while before Italian unification it was mainly the Grand Duchy of Tuscany that resorted to such practices, thanks to the remote origins from Leghorn of many of these communities.

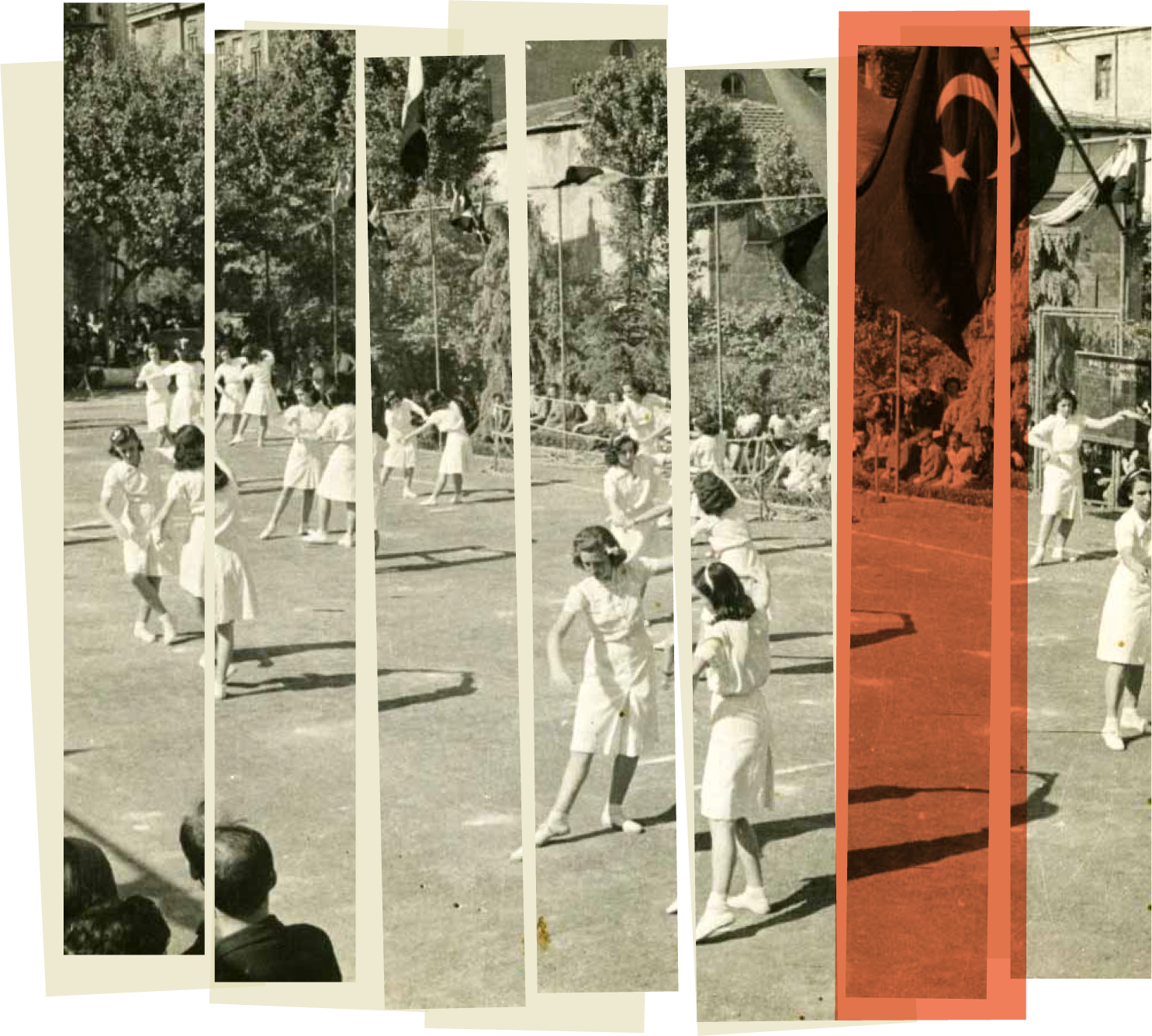

What is certain is that in the aftermath of Italian unification, while the North African coasts—Egyptian, Tunisian, and Algerian—began to welcome a new and profoundly different wave of Italian emigration, initially consisting mainly of political exiles and professionals and then, increasingly, of manual laborers, the ties between Italy and the nominally Italian Jewish communities of the Mediterranean began to be undermined by growing French political and cultural influence. Thanks to the educational and philanthropic work of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, which made the teaching of French one of its strengths, and to French economic and commercial power and political expansionism, Paris succeeded in becoming the natural point of reference for much of Mediterranean Jewry. This led to the spread of French as the main spoken language, both at home and in public, replacing Italian.

Despite the progress of French influence, however, there were many Levantine, Egyptian, and Tunisian Jews who continued to look to Italy as their natural national and cultural reference point. On this point, it is of interest the case of the Jewish community of Leghorn origin in Tunis, the so-called Grana, which always remained proudly separate from the Jewish community of Tunisian origin and proud of its cultural and family ties with Italy. In this situation, during the liberal era, Italian governments showed a certain interest, albeit intermittently, in these communities of distant Italian origin or more recent Italian citizenship. The diplomatic and consular reports from Thessaloniki, Constantinople, Smyrna, Aleppo, Alexandria, and Tunis described these communities, which were hard-working and sober, in positive terms, judging them to be elements that contributed to Italian prestige in the eastern Mediterranean.

Italy's "Sephardic policy" and the beginning of Middle Eastern and Balkans Jewish immigration

The attention of the governments in Rome to these communities increased in the early 20th century and even more so in the aftermath of the conquest of Libya and the First World War. In the new geopolitical situation, Italian diplomacy, strengthened by its control of the important Jewish community of Rhodes, sought to develop its own “Sephardic policy.” The aim was to counter French hegemony over the Jewish communities of the Mediterranean See and, at the same time, to offer an alternative to the Zionist projects supported by the British, which were rather unpopular among Mediterranean Jews at the time. Several political initiatives launched by Italian governments in those years were an expression of this attempt at political projection: the mission entrusted, immediately after the end of the war, to Captain Angelo Levi-Bianchini among the Sephardic communities of the eastern Mediterranean, which tragically ended with his assassination in Syria in August 1920; the appointment of David Prato as chief rabbi of Alexandria, Egypt, in 1927: a choice that, while part of a tradition that had seen other Italian rabbis leading the community of Alexandria in previous years, gave rise to a fruitful synergy with Italian foreign policy, leading to repeated meetings between Prato and Mussolini himself during the 1930s; finally, the attempt, which took shape between 1928 and 1938, to establish a rabbinical college in Rhodes, which could serve as a reference point for the entire Mediterranean Jewish community, promoting cultural ties with Italy.

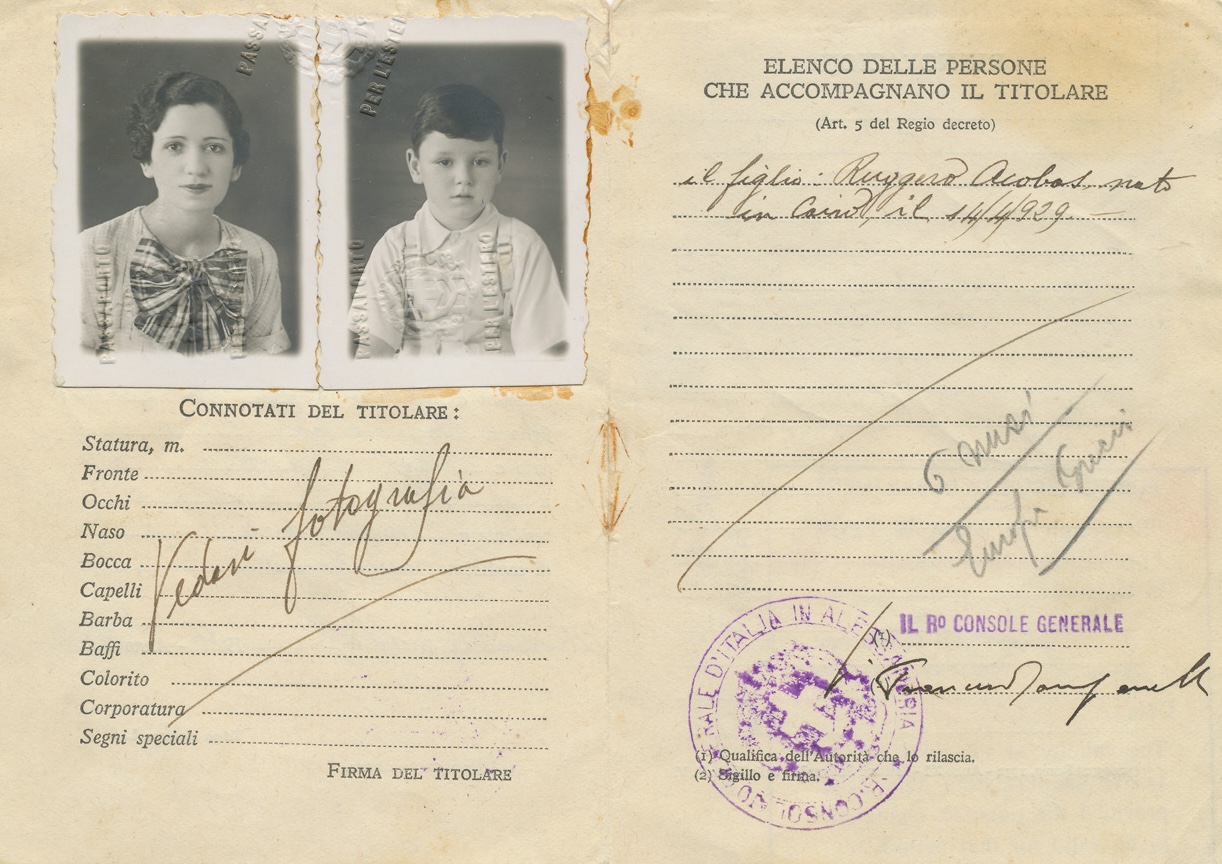

The results of these disparate initiatives promoted in relation to Sephardic Judaism were not particularly significant. This was also because, especially after the advent of fascism, ‘Sephardic policy’ was only one of the many contradictory aspects of Italian Middle East policy. It alternated between openness to the Zionists, more constant support for Arab nationalism, demands to defend Catholic positions in the region, and ambitions to make Italy an ‘Islamic power’: a heterogeneous and fluctuating policy whose only real unifying aspect was the attempt to undermine British hegemony in the eastern Mediterranean. Certainly, at the time of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and in the years immediately following, the Italian consuls in the region, like those of the other European powers, were authorized to generously distribute certificates of citizenship and protection to numerous groups of local Jews who, very often, had no previous connection with Italy. In this way, they further extended a practice that, as we have seen, had been in place for a long time.

In light of these aspects and the long-standing and complex ties between Italy and part of the Jewish population of the Near East, it is not surprising that, during the 20th century, Italian cities, primarily Milan and Rome, became destinations for permanent or temporary migration by groups of Jews from the Balkans, the Middle East, and North Africa. As early as 1911, following the Italian conquest of Lybia and the Italo-Turkish War, a number of Jews from Tripoli arrived in Milan along with a small group of Jews from Istanbul, fleeing the anti-Italian and anti-European sentiment that had spread throughout the capital of the Empire. During the troubled interwars period, this phenomenon resumed on a larger scale. At the beginning of the 1930s, there were about two thousand Eastern Jews in Italy, mainly from cities in Asia Minor, such as Smyrna, which had been devastated by the Greco-Turkish War, and Thessaloniki. Faced with the disintegration of the multi-ethnic and multi-confessional Ottoman society, some of them had identified Italy as a natural landing place to escape the political turmoil in the region and to relaunch their commercial activities. Of course, these were still very limited numbers compared to those who would arrive after World War II, faced with the rapid disappearance of Judaism in Arab countries, and even more so when compared to those who went to France, Great Britain, Latin America, or Israel. Many of the dynamics that determined their arrival in Italy, starting with cultural and linguistic ties and, above all, the issue of Italian citizenship enjoyed by some of these Jewish families, however were largely overlapping.

Bibliography

S. Minerbi, L’azione diplomatica italiana nei confronti degli ebrei sefarditi durante e dopo la I guerra mondiale (1915-1929), in «La Rassegna mensile di Israel», XLVII, 1981, pp. 86-119.

A. Molho, Ebrei e marrani fra Italia e Levante ottomano, in C. Vivanti (a cura di), Gli ebrei in Italia, vol. II, Dall’emancipazione a oggi (Storia d’Italia. Annali 11), Einaudi, Torino, 1997, pp. 1011-1043.

I. Papo, L’immigrazione ebraica in Italia dalla Turchia, dai Balcani e dal Mediterraneo orientale nella prima metà del XX secolo, in L. Picciotto (a cura di), Saggi sull’ebraismo italiano del Novecento in onore di Luisa Mortara Ottolenghi, numero monografico de «La Rassegna mensile di Israel», LXIX, 2003, pp. 93-126.

A.M. Piattelli e M. Toscano (a cura di), Memorie di un rabbino italiano. Le agende di David Prato (1922-1943), Viella, Roma, 2022.

S.A. Stein, Extraterritorial Dreams: European Citizenship, Sephardi Jews, and the Ottoman Twentieth Century, University of Chicago Press, Chicago-London, 2016.

F. Trivellato, The Familiarity of Strangers: the Sephardic Diaspora, Livorno, and Cross-cultural Trade in the Early Modern Period, Yale University Press, New Haven-London, 2009.

P. Zanini, Tra due diaspore: ebrei levantini ed egiziani in Italia (1948-1957), in «Mediterranea», XIX, 2022, pp. 41-68.