Jews of Tunisia

From antiquity to the French protectorate

The Jewish presence in Tunisia dates back to antiquity, with historical texts and archaeological evidence confirming the existence of a stable community as early as the second century BCE that had settled in the region of Carthage and on the island of Djerba. During the Middle Ages and modern times, the Jews of Tunisia were integrated into the Islamic world, playing a significant role in local trade and crafts. In 1710, following the arrival of a group of Iberian Jews from the Italian port of Livorno, the Jewish population split into two distinct communities: the Tunisian Jews (Twansa) and the Livornese Jews (Grana). The Grana, a minority, enjoyed economic and legal privileges; protected by Tuscan consuls, they were active in international trade, entrepreneurship, and economic mediation with Christian countries.

In the nineteenth century, Tunisian Jews were influenced by the modernizing reforms of the Beys of Tunis, who proclaimed religious freedom and equal rights in 1857. However, many also benefited from the increasing European penetration in Tunisia, working as translators, dragomans, and mediators. The establishment of the French protectorate in 1881 opened a new era, offering unprecedented opportunities for social mobility. The Jewish population grew rapidly due to high birth rates and better medical coverage. In 1921, the first official census recorded 48,000 Jews (regardless of nationality), which increased to 66,000 in 1936 and 95,000 in 1946.

This demographic growth was accompanied by a gradual integration into the European world, reinforcing the national pluralism of the Jewish population. Most of the Livornese Jews (between 3,000 and 5,000) adopted Italian citizenship in 1861 and formed a prosperous, educated bourgeoisie with strong ties to Italy. Many Tunisian Jews, however, leaned towards France, especially after the Morinaud Law of 1923 facilitated individual naturalization. By the eve of World War II, 7,000 Jews had already become French citizens; by the time of Tunisia’s independence, this number had risen to 25,000. A small minority took British citizenship, while most local Jews retained their status as subjects of the Bey.

Evolution during the colonial period

Evolution during the colonial period

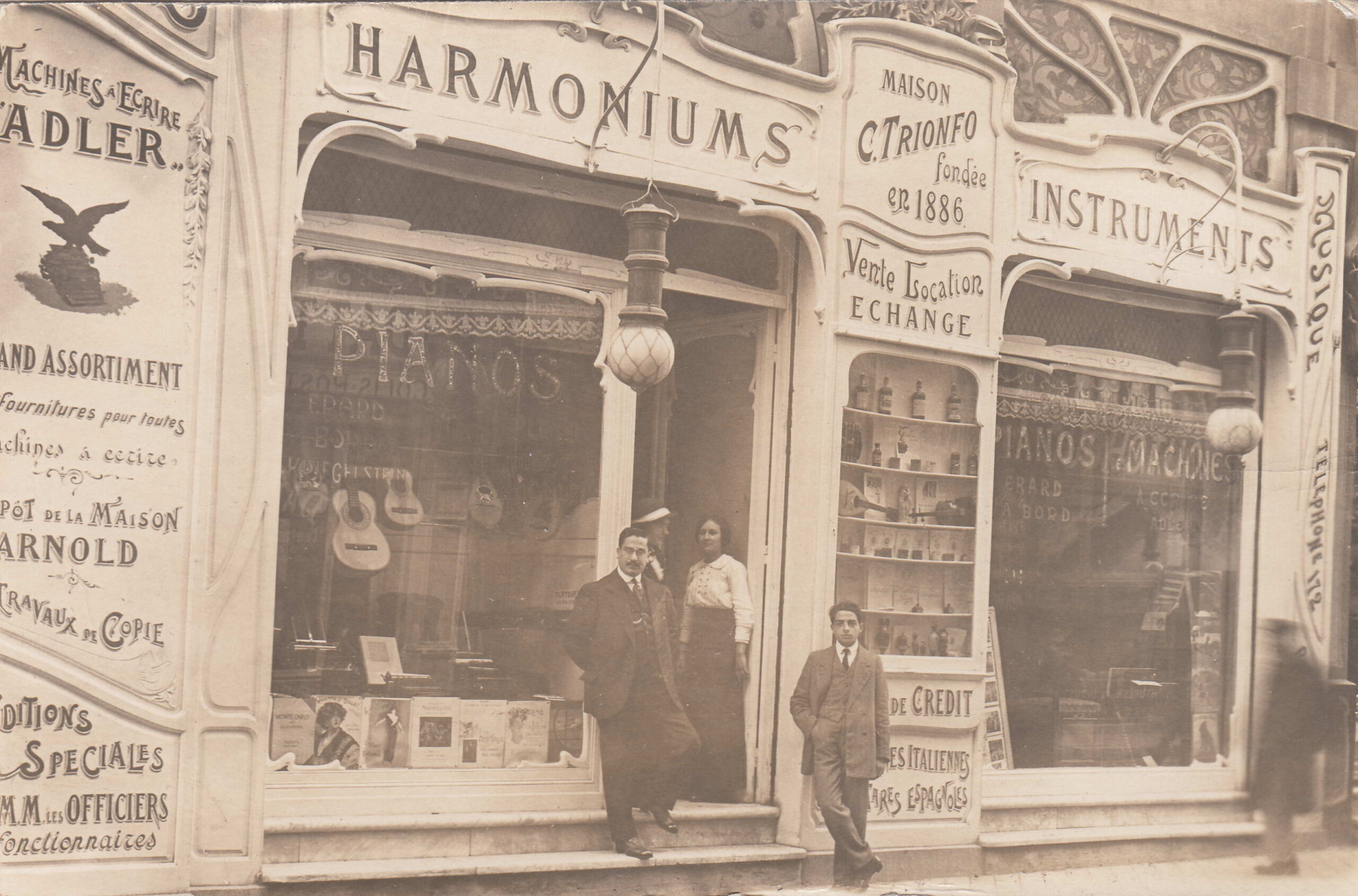

While Jews continued to be well-represented in commercial professions, the country’s modernization opened the door to new occupations, such as plumbers, glaziers, electricians, and printers. At the beginning of the twentieth century, many Jews were also active in the entertainment industry, owning theaters and cinemas. Education in protectorate schools, which allowed access to European universities, led to the emergence of a new middle class: many Jews became lawyers, doctors, pharmacists, or employees in local administration. The old Jewish-Livornese bourgeoisie was joined by a new Jewish bourgeoisie of Tunisian and French nationality. However, the majority of the population continued to live in chronic poverty, at least until the 1930s.

Access to modern culture also led to the Westernization of customs. French gradually replaced Arabic as the everyday language. There was a decline in religious observance, as evidenced by the increasingly frequent complaints from rabbis about the violation of dietary laws, the opening of shops on the Sabbath, and the indifference to traditional holidays. In particular, the education of girls marked a significant break with traditional Jewish society: the age of marriage rose, consanguineous marriages became rarer, and the number of children per family decreased.

While public opinion among the Jewish population had long been divided between traditionalists and modernists, the twentieth century saw the emergence of new political ideas. Zionism spread in the country thanks to numerous newspapers, the creation of a coordinating body in 1920 (the Fédération Sioniste de Tunisie), and the growth of youth associations such as the UUJJ (Union Universelle de la Jeunesse Juive) scouts. On the other hand, part of the intelligentsia embraced communist ideals, especially after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. Within the Tunisian Communist Party (PCT), young Jewish intellectuals in Tunis waged a battle against colonialism and fascism. During the war, many of them faced harsh repression from the Vichy authorities, the fascist consul, and even the Nazi army during the six months of Italo-German occupation (1942–1943). The liberation of Tunisia by the Allied armies on May 6, 1943, led to the abolition of the Vichy racial laws and the restoration of civil rights.

Post-war and independence: Departures and dispersion

The post-war period was marked by the dispersion of the Tunisian Jewish community. After the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism in Tunisia experienced an unprecedented boom. Within a few years, about 25,000 Tunisian Jews had made ‘aliyah, with a total of 50,000 between 1943 and 1970. The exodus of the Jewish minority continued after 1956, following Tunisia’s independence. The new government, led by the nationalist leader Habib Bourguiba, sought to integrate Tunisian Jews into the new nation. With the enactment of the modern “Code of Personal Status,” legal equality was guaranteed to all Tunisian citizens, regardless of religion. This policy of inclusion even allowed a prominent Jew, Albert Bessis (1885–1972), to be elected to the National Assembly. However, the Arabization of the state, social tensions, and the deterioration of relations with France and Israel (especially after the Bizerte crisis in 1961 and the Six-Day War in 1967) led most Tunisian Jews to emigrate. In the decade following Tunisia’s independence, the country’s Jewish population dropped from 58,000 to 18,000 people. About half of the departures were absorbed by France, another half by Israel, and only a small minority headed to Italy, Canada, or the United States. By 2018, the former Tunisian Jewish community had shrunk to a small group, estimated at 1,500 people, concentrated on the island of Djerba and in Tunis. Some historic and religious sites, such as the Ghriba synagogue, continue to attract tourists and pilgrims, especially during Passover and Sukkot. Relations with the Tunisian Muslim population are generally peaceful, although terrorist attacks in 2002 and 2023 severely tested the coexistence between the two communities.

Current status of the Tunisian Jewish diaspora

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Tunisian Jewish diaspora was mainly distributed between France and Israel. It is estimated that about 50,000 people emigrated to France between 1950 and 1970, including almost all the intellectual elites, such as the philosopher Albert Memmi (1920–2020), and some members of the middle and working classes, many of whom had already obtained French citizenship during the protectorate. The new arrivals settled in the Paris region (particularly in the neighborhoods of Belleville and Ménilmontant), in southern France (in the cities of Toulouse, Marseille, Nice, and Montpellier), and in the Rhône Valley (in Lyon and Grenoble). Like their Moroccan and Algerian co-religionists, Tunisian Jews who had obtained French citizenship benefited from economic aid provided by the French state to repatriates from former colonies. Enrollment in the French education system and the automatic naturalization of the emigrants’ children facilitated rapid assimilation into the new society. However, the new generations have retained a well-defined cultural heritage, reflected in their language, music, and cuisine. The emigration to Israel involved about 50,000 people, largely from the more modest and traditionalist strata. Other migratory flows led a few hundred exiles to settle in Italy (particularly descendants of the Livornese community) and Canada, giving the Tunisian Jewish diaspora a global dimension.

Bibliography

Olfa Ben Achour, L’émigration des Juifs de Tunisie de 1943 à 1967, Namur, Publishroom, 2019.

Abdelkrim Allagui, Juifs et musulmans en Tunisie: des origines à nos jours, Paris, Éditions Tallandier, 2016.

Sergio Della Pergola, «Structures socio-démographiques de la population juive originaire d’Afrique du Nord», in Jean-Claude Lasry et Claude Tapia (dir.), Les Juifs du Maghreb: diasporas contemporaines, Presses de l’Université de Montréal, Montréal, 1989.

Lionel Lévy, La nation juive portugaise: Livourne, Amsterdam, Tunis: 1591-1951, Paris, France, 1999.

Martino Oppizzi, Les Juifs italiens de Tunisie pendant le fascisme. Une communauté à l’épreuve (1921-1943) , Presses Universitaires de Rennes, Rennes, 2022.

Filippo Petrucci, Gli ebrei in Algeria e in Tunisia, 1940-1943, Giuntina, Firenze, 2011.

Paul Sebag, Histoire des Juifs de Tunisie: des origines à nos jours, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1991.

Patrick Simon and Claude Tapia, Le Belleville des Juifs tunisiens, Paris, Éditions Autrement, 1998.

Memoirs and autobiographies

Sophie Bessis and Leïla Sebbar, Enfances tunisiennes, Tunis, Elyzad, 2010.

Elia Boccara, In fuga dall’inquisizione: ebrei portoghesi a Tunisi: due famiglie, quattro secoli di storia, Giuntina, Firenze, 2011.

Robert Borgel, Étoile jaune et croix gammée, Éditions Le Manuscrit, Paris, 1944.

Paul Ghez, Six mois sous la botte, Paris, France, S.A.P.I., 1943.

Albert Memmi, La statue de sel, rev. ed. and Corr. ed., Paris, Gallimard, 1966.

André Nahum, Le roi des briks, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1992.

Giacomo Nunez, Delle navi e degli uomini, i portoghesi di Livorno: da Toledo a Livorno e a Tunisi, Salomone Belforte Editore, Livorno, 2011.

Nadia Spano, Mabrúk: ricordi di un’inguaribile ottimista, Editori Riuniti, Cagliari, 2005.