Jews of Egypt

The Jews in Egyptian history

Outside of the Land of Israel, Egypt is probably one of the places that has had the longest interaction with the Jewish people. According to the journalist and historian Maurice Fargeon, who lived in Cairo in the early twentieth century and who published one of the first history books on the Jews of modern Egypt, Les juifs en Egypte, in 1938, “every time they were oppressed […], the Jews sought refuge in Egypt, where they were sure to find a cordial and brotherly reception.” The relationship between the Jewish people and Egypt began in biblical times and extended throughout the Middle Ages: think of great personalities like the rabbi and philosopher Maimonides, who was born in Cordoba in 1138 and died in Fustat (Cairo) in 1204. However, during the Ottoman period and until the mid-nineteenth century, Egyptian Jewry remained small—c. 5,000 people in 1840—and relatively unimportant. At that time, most Jews lived in the harat al-yahud (“Jewish quarter”) of Cairo or in smaller urban centers of the Nile Delta, such as Tantah. From late antiquity, Cairo also hosted a Karaite community, which numbered 5,000 people in 1948, and it has always been one of the most Arabized components of Egyptian Jewry.

The birth of modern Egyptian Jewry

It was only after the opening of the Suez Canal (1869) and the economic expansion that Egypt underwent under British colonial rule (1882–1922) that thousands of Jews from all over the Ottoman Empire, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Southern (and to a lesser extent Eastern) Europe migrated to Cairo and Alexandria, as well as to Suez, Port Said and Isma‘iliyah. Thus, the Jewish population of Egypt increased—based on the available records—to more than 25,000 people in 1897 and to at least more than 60,000 in 1937. In a few decades, many of these newly arrived migrants had improved their status, creating a relatively well-off and modern community that became an integral part of colonial and monarchic Egypt up until the 1950s, when it counted around 80,000 people. From a socio-economic perspective, in the first half of the twentieth century, the majority—about 65 percent—of Jews living in Egypt belonged to the middle and lower-middle class, 10 percent to the upper class, and 20 to 25 percent to the lower class. Important dynasties of bankers and entrepreneurs flourished, including the de Menasce family in Alexandria and the Cattaouis and the Cicurels—owners of one of the most famous Egyptian department stores—in Cairo. Others owned small businesses or worked as professionals and were part of that educated, largely urban middle class that developed during the colonial period, to which Muslims, Copts, Armenians, Syro-Lebanese, Greeks, and Italians also belonged.

Nationality and politics

As far as nationality is concerned, in 1927—five years after the end of British rule and the establishment of the constitutional monarchy of King Fu’ad (1869–1936)—33 percent of Jews were Egyptian nationals, 22 percent were of other (mainly European) nationalities, and 45 percent were counted as “others”, which probably means that they were stateless. The possession of a foreign nationality did not mean that they were (all) foreigners to the region: this depended mainly on the system of capitulations, which since early modern times had given juridical and tax privileges to Europeans residing in the Ottoman Empire, including local subjects—particularly Jews and Christians—whose commercial and professional connections helped them to obtain a foreign nationality. Nor should the fact that so many were stateless be seen as exceptional in a context such as Egypt, where the juridical category of nationality was only systematized in 1929, with a law that made it quite difficult for non-Muslims to become Egyptians, and where the capitulations were abolished in 1937. With reference to Italy, in 1917, Egypt hosted 40,198 Italian nationals, of whom 6,629 were Jews. Some of them had moved there from the Italian peninsula, whereas others had become Italians thanks to the capitulations, often by claiming Livornese ancestry. The number of Italians—and, to a more limited extent, of Italian Jews—grew in the subsequent years, reaching a peak of c. 55,000, before declining steadily after the Second World War and the Free Officers’ Revolution (1952) led by Gamal ‘Abd-al-Nasser (1918–1970).

Culture, religion, and society

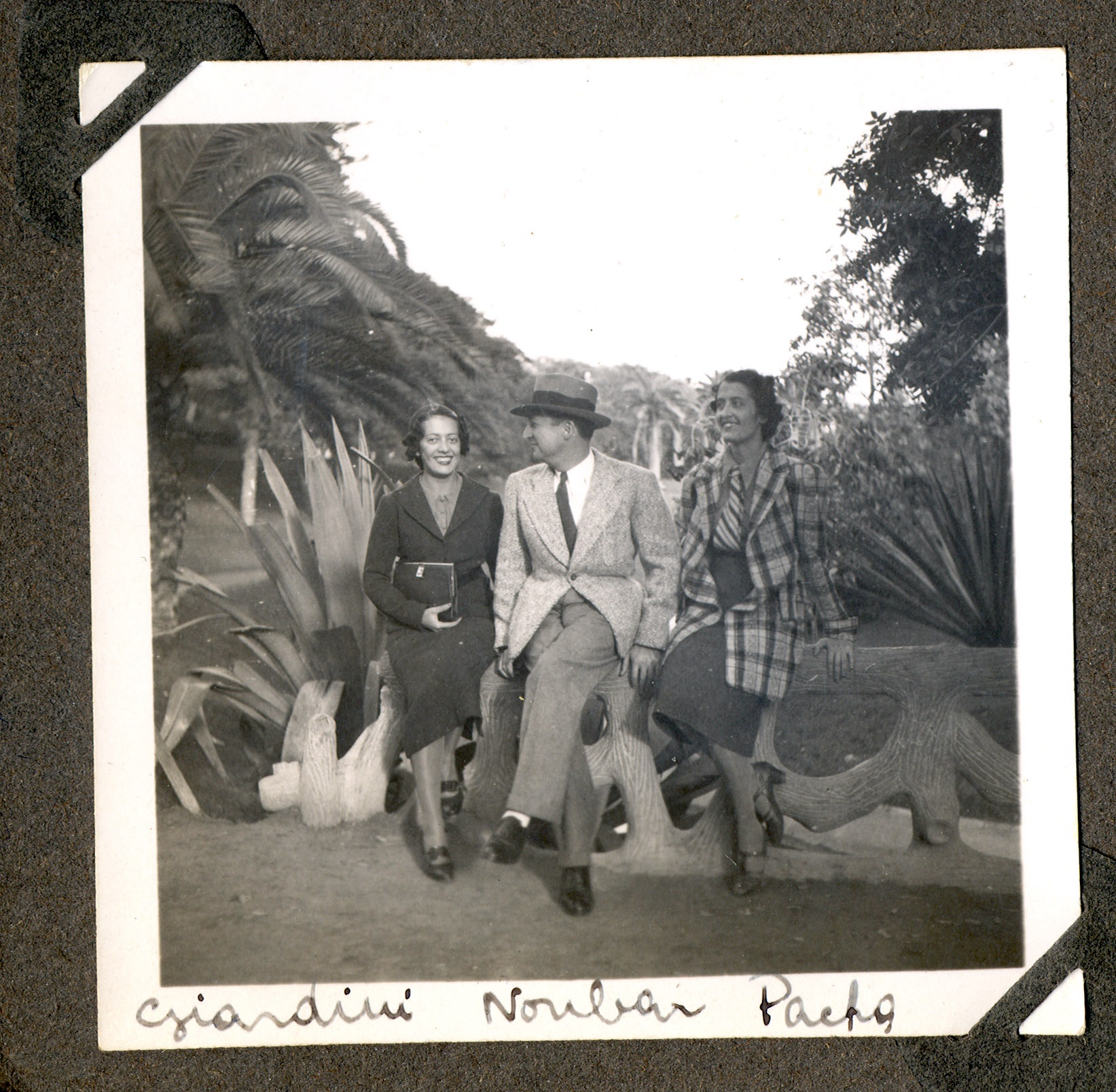

Egyptian Jews were an integral part of Egyptian society, but in some ways, they were seen as “other” from the majority of the Egyptian Muslim population. Due to their different origins, many could converse in French, Italian, Judeo-Spanish, and Arabic (though this language was only spoken by some on a daily basis and in the family). Though feelings of Jewishness were important, the majority were not strictly observant and followed a relatively open approach to Judaism and the halakhah (Jewish law). Conversion to Islam or Christianity was uncommon, and marriage and family life reflected norms of middle class respectability and a rather traditional gender division. Aside from sectors of the lower classes, Jews tended to live in the more modern neighborhoods of Cairo and Alexandria: ‘Abbasiyah, Zamalek, Garden City, or Ramleh. Relations with non-Jewish Egyptians were frequent and took place in school, as well as at work, in places of social gathering—such as clubs or cafés, for example, Groppi in Cairo and Pastroudis in Alexandria—or at home for the many who had Muslim neighbors or employed domestic staff. Episodes of anti-Jewish violence—often driven by economic rivalries, such as the famous Alexandrian case of ritual murder accusation known as the Fornaraki affair (1881)—had already occurred in the colonial period, but on the whole, relations between ethno-religious groups remained good. Deeper anti-Jewish feelings only emerged in the mid-1930s—during the reign of King Faruq (1920–1965), with the consolidation of political movements like Young Egypt and the Muslim Brotherhood—and after the 1948 war.

Migrations and the decline of Egyptian Jewry

Because of their recent migration and the fact that many were not Egyptian nationals, only some Jews were involved in domestic politics. Examples include the satirist and essayist Ya’qub Sannu’ (1839–1912), who was partly of Livornese ancestry; the president of the Jewish community of Cairo Joseph Cattaoui (1861–1942), who acted as minister of finance and communication between 1924 and 1925, and the lawyer Léon Castro (1884–1954)—a friend of Sa’ad Zaghlul (1858–1927), the leader of the Wafd Party. Even though Zionist groups had existed since the late nineteenth century, Zionism only appealed to a minority of Jews and did not become more relevant until the late 1930s and 1940s. Among the most important pro-Zionist newspapers were Israël and La Tribune juive. Around the 1940s, communist and socialist ideas started to appeal to the younger generations, and—as elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa—some Jews, for example, Henri Curiel, became important figures in Egyptian Communism.. Intorno agli anni Quaranta, idee comuniste e socialiste iniziarono ad attrarre le generazioni più giovani e – come altrove in Medio Oriente e Nord Africa – alcuni ebrei, ad esempio Henri Curiel, divennero importanti membri del comunismo egiziano.

With the 1948 War, the Free Officers’ Revolution, the end of the monarchy, and then the regional pan-Arab and anti-colonial struggle, waves of migration began. In some cases, Jews—as well as European nationals—were expelled and accused of anti-Egyptian activities, often after being interned in camps such as Camp Huckstep, near Cairo. More Jews left after the so-called Lavon affair—an act of espionage on Israel’s part that took place in 1954—and at the time of the 1956 Suez War. By the early 1960s, only around 2,500 Jews remained in Egypt, and their number would continue to decrease in the following years. Almost all of them resettled in Israel, Europe—France, but also the United Kingdom and Italy—the United States, Brazil, and Australia. More precisely, the relative majority of Egyptian Jews made ‘aliyah—c. 14,000 between 1948 and 1955, and 16,500 more between 1956 and 1966—which means that in the end, about forty percent settled in Israel. Concerning Italy, it is difficult to give precise numbers, also because a few hundred of the arrivals were Jews with Italian nationality—who mainly settled in Milan—and many more had an Italian laissez-passer and in most cases did not remain in the country.

Nowadays, there are a few dozen elderly Jews in Cairo. For those born in Egypt and now scattered all over the world and their descendants, Egypt remains a lost homeland to remember with sorrow, nostalgia, or anger. Migrant associations in Paris and Tel Aviv, synagogues in Israel and the United States, dozens of books—some in Italian, like Il chilometro d’oro (2006) by Daniel Fishman and La casa sul Nilo (2022) by Denise Pardo—and a few documentaries transmit what is perceived as the lost world of the Jews of Egypt.

Bibliography

Baussant, Michèle. “‘Voir les voix’: les Juifs d’Égypte d’une rive à l’autre. Europe, Israël et États-Unis”, Conserveries mémorielles, 25 (2922), accessibile all’indirizzo: https://journals.openedition.org/cm/5565?lang=en.

Beinin, Joel. The Dispersion of Egyptian Jewry: Culture, Politics and the Formation of a Modern Diaspora (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

Krämer, Gudrun. The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914-1952 (Londra: IB Tauris, 1989).

Ilan, Nahem (a cura di). Mitzrayim (“Egitto”) (Gerusalemme: Istituto Ben-Tzvi, 2008) [ebraico].

Landau, Jacob. Jews in Nineteenth-Century Egypt (New York: New York University Press, 1969).

Miccoli, Dario. Histories of the Jews of Egypt: An Imagined Bourgeoisie, 1880s-1950s (Londra: Routledge, 2015).